Debates over how America’s public lands should be managed are as old as the system itself, dating back to the early 1900s when President Teddy Roosevelt pioneered the current system. Disagreements have often centred on the balance between energy or resource development and protecting wild places for recreation and wildlife. At Patagonia, we’ve fought for decades to defend our most treasured wild places – those areas with exceptional characteristics that provide the greatest value when simply left untouched. In countless battles over the years, we’ve supported grassroots groups and local people, all united by the fundamental idea that our federal public lands belong to all Americans and represent a core part of our country’s heritage.

The fact is, a resounding majority of Americans support protection of our public lands. In a 2016 Harvard Kennedy School study, more than 93% of respondents across the country said it’s important that historical sites, public lands and national parks be protected for current and future generations.

But recently, ideas are resurfacing that seek to undermine our public lands. These efforts use misleading appeals for “states’ rights” and flawed economic information to remove protections from some of our most special places in order to extract short-term profit. Backed by powerful fossil fuel and extractive industry interests, this systematic, well-organised and multifaceted movement began at the state level and now enjoys support at the highest level of government.

“This would amount to theft from the American people.”

If these ideas take hold, America could lose one of its most unique and enduring traditions. This isn’t a political issue, it’s a matter of Americans keeping the great promise of their country for their children and grandchildren. Attempts to undermine America’s tradition of balanced stewardship are fundamentally out of step with popular sentiment favouring protections for public lands, the enormous popularity of recreation on public lands and the huge economy supported as a result – among many other factors.

Right now, a broad coalition of sportsmen’s organisations, small local businesses, the entire outdoor industry, national and grassroots conservation groups and individuals all over the country are speaking up in defense of America’s public lands heritage for all citizens now and in the future.

We all have a stake in the future of our public lands, and we need everyone to get involved. I hope this article helps shed light on some key concepts about public lands and what it means to manage them for the greatest possible benefit for all Americans.

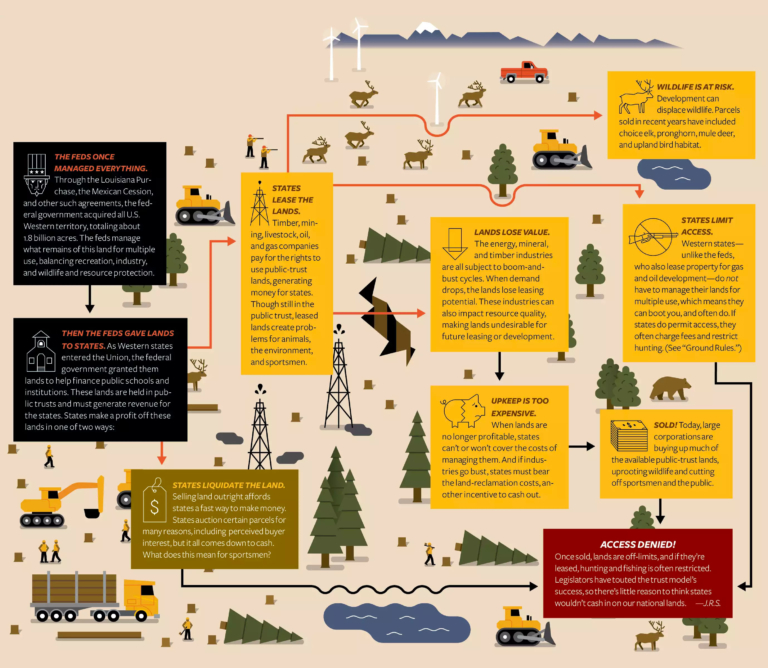

Illustration: Field & Stream

Illustration: Field & Stream

Who owns US federal public lands?

Americans do. Federal public lands encompassing 640 million acres spread across all 50 states are owned by every American. These lands are managed by professional land managers in several federal agencies for our direct benefit and the benefit of all future generations – a responsibility known as stewardship. This is in contrast to state-owned lands, which can be sold at any time to the highest bidder. Historically, when states have been entrusted with public lands by the federal government, many have had no problem with selling those lands for a profit to private corporations and developers. In fact, to date, states have sold 70% of the public trust lands placed under their control to the highest bidder.

Why should all Americans care about public lands?

As public lands owners, Americans all have a stake in their future. This system represents one of America’s most unique and enduring traditions: the bold idea that heritage does not solely belong to current citizens, but to all future generations as well. The federal lands system includes forests, lakes, rivers and streams, deserts, mountains, plains, wetlands and more.

I think Teddy Roosevelt put it well: “We have fallen heirs to the most glorious heritage a people ever received, and each one must do his part if we wish to show that the nation is worthy of its good fortune.”

Giant Sequoia National Monument protects 34 groves of ancient trees—the world’s largest species—that only grow naturally in a 60-mile stretch of the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada. Today, these spectacular trees survive in only about 70 groves and are currently the only known trees with nesting cavities large enough to support the California condor. The last breeding pair in the wild was found near the monument. The rings of these trees contain multi-millennial records of past environmental changes. Photo: Jerome Gorin.

Giant Sequoia National Monument protects 34 groves of ancient trees—the world’s largest species—that only grow naturally in a 60-mile stretch of the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada. Today, these spectacular trees survive in only about 70 groves and are currently the only known trees with nesting cavities large enough to support the California condor. The last breeding pair in the wild was found near the monument. The rings of these trees contain multi-millennial records of past environmental changes. Photo: Jerome Gorin.

How are our public lands managed?

On behalf of all American citizens, the U.S. government bears responsibility for stewardship of our federal public lands – which includes collecting public and scientific input under processes defined by the law to make decisions about what lands are used for what purposes. As enshrined in the laws and American traditions dating back to the early twentieth century, the solemn concept of stewardship means considering long-term benefits not only for all Americans now, but for all future generations as well.

For example, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management’s (BLM) official mission is “to sustain the health, diversity and productivity of the public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations.”

While some federal lands may be appropriate for development, other areas with pristine or vulnerable ecosystems popular with millions of Americans for recreation should receive strong protection. Put simply, many places simply provide the greatest overall value when threats of environmental degradation are not present.

The protected coastal waters of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are larger than all the national parks combined. The area provides a home to 7,000 marine species—half of which are unique to the Hawaiian island chain – and 14 million seabirds. It is also an important landscape for understanding Polynesian culture. Photo: Ian Shive.

The protected coastal waters of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are larger than all the national parks combined. The area provides a home to 7,000 marine species—half of which are unique to the Hawaiian island chain – and 14 million seabirds. It is also an important landscape for understanding Polynesian culture. Photo: Ian Shive.

What are the major threats our public lands face right now?

State-level pressure driven by extractive industries to dismantle protections for public lands has bubbled up into mainstream politics in recent years. Several key concerns require our vigilance and action.

Land transfer proposals: Anti-public lands advocates argue that these lands should be “returned to state control,” which they claim would allow decisions about land use to be made at the local level. But if a state owns the land, it’s no longer owned by the American people. This would amount to theft from the American people – severely limiting our access for recreation, including hunting and fishing, by putting control into the hands of a few wealthy special interests, rather than keeping our lands in public hands. And it would severely damage the thriving outdoor recreation economy that supports 7.6 million American jobs.

Truth: This kind of federal land transfer has occurred before, with 156 million acres entrusted to the states as they entered the union. To date, those states have sold off 70% of that land to the highest bidder at auction

Removal of national monument protections: The Trump administration has threatened to remove or reduce protections from 27 national monuments through an unprecedented review conducted by the Secretary of the Interior. As of now, these lands and waters – stretching from northern Maine to Hawai‘i – provide enormous recreational and ecological value, now and for future generations. If monument status is removed, boundaries changed or protections reduced, they could be opened up for development and forever changed.

Truth: 80% of Western voters want to maintain designations of public lands as national monuments – and by a 15-point margin, voters see the Bears Ears National Monument designation as a good thing.

Prioritising oil and gas development on BLM lands: The current administration, bolstered by supportive members of Congress funded by the fossil fuel and mining industries, appears poised to significantly increase the availability of sensitive public lands to oil and gas and mining leases. Trump changed the very mission of the chief agency responsible for public lands management to emphasize the fossil fuel industry. But oil and gas activities are already extensive on public lands, generating billions of dollars in government revenue every year.

Truth: More than two-thirds (68%) of voters in Western states support prioritizing public lands production (compared with 22% who support prioritizing energy production).

Undermining longstanding, bipartisan federal law: Laws like the Antiquities Act of 1906, the Wilderness Act of 1964, the National Environmental Protection Act of 1970, Endangered Species Act of 1973 and Federal Land Policy & Management Act of 1976 that codify and enable responsible stewardship of public lands were passed with resounding bipartisan support. The United States was among the very first countries in the world to enshrine environmental priorities in federal law. Increasingly, however, we’re seeing those laws eroded through lax enforcement, loopholes and outright lies about the impacts of public land protection.

Truth: A large majority of Americans—90%—support upholding the Endangered Species Act, and more than 60% think it would be wrong to weaken wildlife protections and air and water regulations to bolster the energy industry.

Vermilion Cliffs National Monument is a geography of sandstone slickrock and rolling plateaus. California condors nest here following an optimistic reintroduction, and the sunsets are some of the most spectacular in the American west. Photo: Bob Wick/Bureau of Land Management.

Vermilion Cliffs National Monument is a geography of sandstone slickrock and rolling plateaus. California condors nest here following an optimistic reintroduction, and the sunsets are some of the most spectacular in the American west. Photo: Bob Wick/Bureau of Land Management.

What are the most common public lands uses?

Our public lands are used significantly for recreation. Public lands are basic infrastructure for outdoor recreation. They play host to 71% of climbing and 43% of paddling done in America, and they also contain nearly 200,000 miles of hiking trails and 13,000 miles of mountain biking trails.

As a result, outdoor recreation is America’s fourth-largest industry – powering $887 billion in annual consumer spending and 7.6 million jobs (compared with 180,000 jobs from oil and gas extraction). Americans spend more on outdoor recreation than on electronics, pharmaceuticals or automobiles.

Federal law explicitly requires that public lands be managed for multiple-use – defined as the “management of the public lands and their various resource values so that they are utilised in the combination that will best meet the present and future needs of the American people.” That means public lands are used for all kinds of things, depending on their characteristics, including energy development, livestock grazing, mining, timber production, wildlife management, scientific study, preservation of cultural resources and outdoor recreation.

To be clear, there’s no shortage of oil and gas leasing and development on public lands, as those activities generated $230 billion in revenues for the U.S. government in 2015. Meanwhile, just one-sixth of all public lands have been given the highest level of protection: inclusion by Congress in the National Wilderness Preservation System.

Does protecting public lands help the economy or hurt it?

Not only do protected public lands power an $887 billion outdoor economy and support 7.6 million jobs, but protected areas also significantly boost the economies of communities nearby. Studies show that rural areas in the West close to protected federal lands perform better on average than areas without protected federal lands in a variety of economic measures, including per capita income and employment.

Basin and Range National Monument is known for its lunar-like landscapes, rock art, Native American sites and 19th century settlements. Roughly double the size of the city of Los Angeles, it remains the most undisturbed corner of the Great Basin region, which extends from the Sierra Nevada Mountains to the Colorado Plateau. The existing monument preserves 13,000 years of human history in addition to climbing, hiking, bicycling, camping and hunting opportunities. Photo: Tyler Roemer.

Basin and Range National Monument is known for its lunar-like landscapes, rock art, Native American sites and 19th century settlements. Roughly double the size of the city of Los Angeles, it remains the most undisturbed corner of the Great Basin region, which extends from the Sierra Nevada Mountains to the Colorado Plateau. The existing monument preserves 13,000 years of human history in addition to climbing, hiking, bicycling, camping and hunting opportunities. Photo: Tyler Roemer.

What is a national monument?

National monuments include some of America’s most iconic places. These are natural or man-made places set aside for permanent protection because they contain unique and irreplaceable cultural, ecological, economic and recreational value. Like national parks, national monuments sit at the top of the list of places worth protecting for our children and grandchildren – and they also drive enormous economic benefits for nearby communities, improving income, employment and population growth.

Unlike the creation of national parks, which require an act of Congress, national monuments can be established by U.S. presidents under the authority granted by the Antiquities Act of 1906. They are established after significant public and community input. National monuments can be managed by a number of federal agencies, and sometimes they’re managed jointly.

America’s 157 national monuments range from a few hundred acres to around one million acres – in all, a tiny fraction of our 640 million total acres of public lands. Out of the 10 most popular national parks, five were first established as national monuments: Acadia, Grand Canyon, Teton, Olympic and Zion.

Who supports protecting public lands?

Voters: In every Western state, 68% of voters support a greater emphasis on public lands protection rather than energy production (22%) – and 70% identify as conservationists.

Native tribes: Many public landscapes hold sacred value for Native American tribes. Recently, tribes and tribal coalitions have provided leadership in campaigns for the protection of places like Bears Ears National Monument, proposing collaborative management with the federal government to protect important natural and cultural resources, and to keep the land open to ongoing traditional uses vital to Native American communities that have lived on the land for thousands of years.

Sportsmen: 81% of hunters and anglers across party lines consider themselves conservationists—and 90% say conservation issues are important in support for an elected official.

Businesses: Hundreds of companies have advocated for protecting public lands because their business depends on outdoor recreation and because protected wild places provide benefits to their employees and serve as an incredible recruiting and retention tool to attract top talent.

Carrizo Plain National Monument is known for its spectacular wildflower blooms, and remains the single largest native grasslands in California. Three hundred years ago this area was home to antelope and elk that grazed on the flowers each spring. Located only 170 miles from Los Angeles, this area offers visitors a chance to experience diverse wildlife and plant species, many of which are threatened or endangered. Photo: Zeiss4Me.

Carrizo Plain National Monument is known for its spectacular wildflower blooms, and remains the single largest native grasslands in California. Three hundred years ago this area was home to antelope and elk that grazed on the flowers each spring. Located only 170 miles from Los Angeles, this area offers visitors a chance to experience diverse wildlife and plant species, many of which are threatened or endangered. Photo: Zeiss4Me.

What 'Public Trust' here.

Banner image – The San Gabriel Mountains are visible from Los Angeles, but their striking geography and ecological diversity still feels wild and far from such concentrated civilization. The range has also been significant for Native Americans, Spanish missionaries and early settlers. Millions of people use the trails, streams and canyons each year. Photo: Taylor Reilly.

____________________________________________________________________

Author Profile