Photographer Paolo Pellegrin captured the aftermath of the wildfires that burned through Australia in 2019.

Australia has burned before.

In fact it’s burned for thousands of years. The First Australians used fire culturally to hunt and to manage the land, and many of Australia’s endemic species such as its iconic eucalypts use fire to propagate and grow. But no other recorded fires have been as destructive as the one Australia saw last summer.

Australia’s Black Summer started the winter before. Fires broke out in August, unseasonably early, when the country was in the grip of drought. By the time summer rolled around, the country was dry as a chip and already burning. When record heat drifted in from the continent’s interior, those fires roared.

New Year’s morning on the NSW South Coast saw holidaymakers huddled together on beaches with their pets, driven to the waterline by flames. Those images were burned into the psyche of Australians. We’d seen fires before, but nothing like this. Thirty-four people would die, three billion animals would perish or be displaced, more than 12.6 million hectares would burn and nearly a billion tons of carbon dioxide would be spewed into the atmosphere. The scale defied comprehension. The smoke would make it all the way to South America.

The fires weren’t even out before the ideological debates began. Conservative politicians and commentators deflected immediately, blaming the fires on a spate of arson and poor forest management. They failed to mention that 2019 was the hottest, driest year ever recorded in Australia. They flat out denied there was a link between the fires and climate change. They skimmed over the fact that Australia is the world’s biggest exporter of both coal and gas. They ignored our role as one of the leading saboteurs of global climate action.

On that front little has changed. The focus in the aftermath of the fires was how Australians would adapt to a future where these supercharged fires occurred more regularly. There was little political will to address the root cause: the burning of fossil fuels.

The rains came in February and Australia switched from fire to flood. The land was scarred, as were Australians themselves. For most, climate change had been an abstract concept, a looming threat that would manifest some way, one day, on an arbitrary timeline. But with the Black Summer it had arrived. Paolo’s photos provide stark testament to this.

In the year since the fires, as Australia, its people and its flora and fauna slowly recovered, the challenge to address the big issues crystallised by the fires has in many ways fallen to small grassroots groups. Patagonia is working with Indigenous groups using cultural burning practices to manage bushfire threats and protect country. We’ve backed coastal activists pushing back against the continuing expansion of the offshore gas industry, and we’ve worked with local communities in building independent, renewable energy networks. None of these groups are resigned to the Black Summer becoming “the new normal.”

Captions and images by Paolo Pellegrin. Paolo Pellegrin is a photojournalist who has documented natural disasters and conflicts in places like the United States, Romania, Indonesia, the Antarctic and more.

These rock formations made me think of the time, many years ago, when I read Bruce Chatwin’s book The Songlines. Upon that hill, with the landscape seemingly infinite, I felt this was a sacred place. I could imagine this was a place where Indigenous Australians lived over millennia. Imlay Road (en route to Bombala), Bondi State Forest, NSW.

These rock formations made me think of the time, many years ago, when I read Bruce Chatwin’s book The Songlines. Upon that hill, with the landscape seemingly infinite, I felt this was a sacred place. I could imagine this was a place where Indigenous Australians lived over millennia. Imlay Road (en route to Bombala), Bondi State Forest, NSW.

This photo speaks to the huge loss of life during the fires. There is something about the sheer scale of loss over this vast continent that is a bit incomprehensible to me. The image also captures the interconnectedness of habitats: even if animals survived, they might have lost their food source, shelter and protection. Bondi State Forest, NSW.

This photo speaks to the huge loss of life during the fires. There is something about the sheer scale of loss over this vast continent that is a bit incomprehensible to me. The image also captures the interconnectedness of habitats: even if animals survived, they might have lost their food source, shelter and protection. Bondi State Forest, NSW.

This image speaks to human loss. There is a strange beauty to these shapes. Metaphorically, the image touches on the loss of property and homes, but also the toxic waste that results from that. Aluminum streams from a melted ute (pickup), Tumbarumba, NSW (edge of Bargo Forest).

This image speaks to human loss. There is a strange beauty to these shapes. Metaphorically, the image touches on the loss of property and homes, but also the toxic waste that results from that. Aluminum streams from a melted ute (pickup), Tumbarumba, NSW (edge of Bargo Forest).

This image also speaks to the loss of life—the plants and animals that lived in this ecosystem. There could be a parallel to make between the fourth and fifth image; they somehow speak to each other—one shows nature, which will regrow, and the other shows waste, which will inevitably be absorbed into the land. Snowy Mountains Highway, Kosciuszko National Park, NSW.

This image also speaks to the loss of life—the plants and animals that lived in this ecosystem. There could be a parallel to make between the fourth and fifth image; they somehow speak to each other—one shows nature, which will regrow, and the other shows waste, which will inevitably be absorbed into the land. Snowy Mountains Highway, Kosciuszko National Park, NSW.

Regrowth. This image represents hope and nature’s ability to regenerate. However, some plants are so sensitive to fires that they will have more difficulty recovering. The fern is a symbol of resilience, continuation of life and nature’s ability to rise from the ashes. Bemm River, East Gippsland, Victoria.

Regrowth. This image represents hope and nature’s ability to regenerate. However, some plants are so sensitive to fires that they will have more difficulty recovering. The fern is a symbol of resilience, continuation of life and nature’s ability to rise from the ashes. Bemm River, East Gippsland, Victoria.

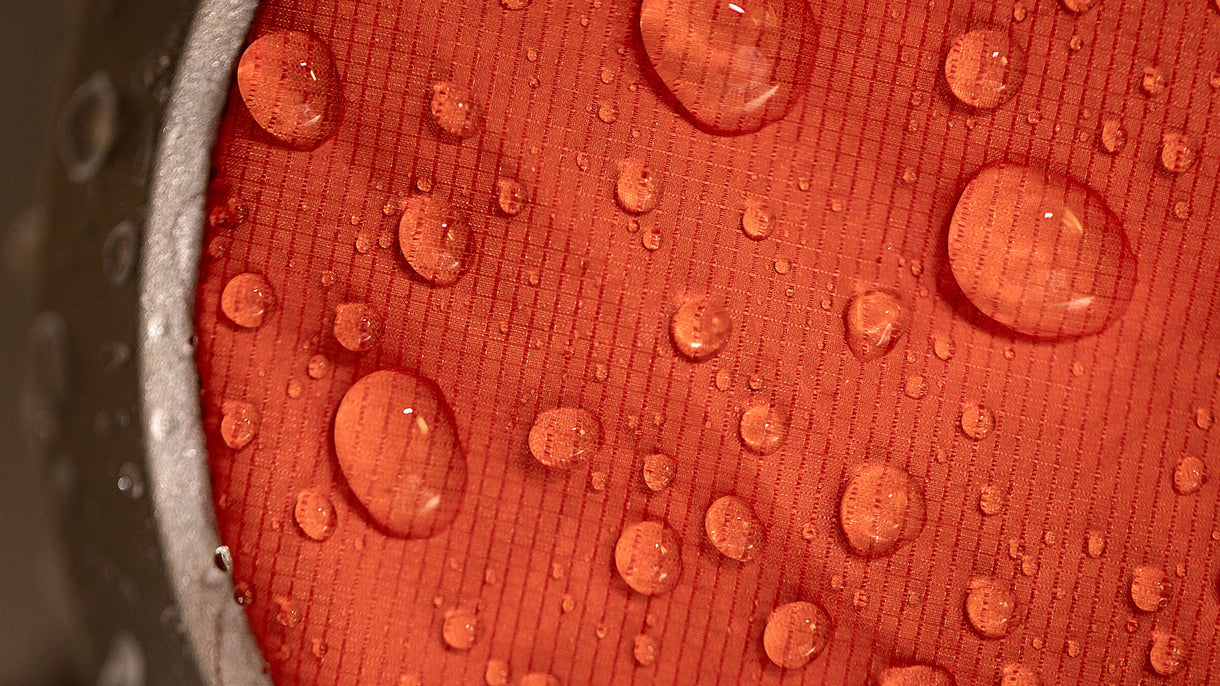

Banner image –

After the fires, the industry tried to salvage the burned trees. The wood harvesting and the intense cutting wasn’t good for the land. I was interested in the contrast of the landscapes: the stumps and the forest behind them. This is a landscape transformed by humans through intense pine harvesting. Scientists say logging, land management and forestry have worsened the fires. Burnt pine plantation (en route to Eden), Bondi State Forest, NSW. Photo: Paolo Pellegrin | Magnum Photos.

____________________________________________________________________

Author Profile