Author’s Note: I want to be clear that these words and ideas represent just one Native person’s perspective; I do not speak for all Natives, nor do I speak for my Tribal Nation.

When I ride my bike, I think a lot about directions: the right-hand turn coming up or the sandy left-hand corner I just navigated, the towering trees above, the trail disappearing beneath me and the long miles ahead that I have yet to cover.

I’ve spent hundreds of hours and thousands of miles contemplating such words, words that—for most English speakers—refer to nothing more than where and what’s around us. But as I started to learn Ojibwemowin, my ancestral language, I began to rethink those directions. The language we speak shapes our understanding of our role in the world, and English, I realised, places us at the center of it … and, in some ways, determines our sense of responsibility and accountability toward it.

My earliest fascination with the English language goes back to a book series, called Amelia Bedelia, I read as a young girl, and in the following years I became obsessed. I journaled, wrote prose, studied grammar and explored ways that writing empowered my ability to express my ideas and internal conflict. What began as curiosity, however, slowly grew into a more complicated relationship.

Names matter. Alexandera pedals through the greenery on the Akiing Anishinaabe trail, an Ojibwemowin name which translates to “Indigenous land,” in English. Duluth, Minnesota. Photo: Hansi Johnson

Names matter. Alexandera pedals through the greenery on the Akiing Anishinaabe trail, an Ojibwemowin name which translates to “Indigenous land,” in English. Duluth, Minnesota. Photo: Hansi Johnson

I’d spent much of my undergraduate education studying American Indians and eventually found myself in a linguistics course on global Indigenous languages. I learned that many of these languages are polysynthetic, meaning words are composed of several morphemes to convey bigger ideas.

Several of these Native languages describe and orient the speaker such that they are interacting within all existence, rather than from its center. They emphasise that the human life is no more valuable than any other life-form, that it can’t exist separately from the rest of the natural world. Ojibwemowin is among them.

One of the early Ojibwemowin phrases I learned was giga-waabamin; it’s what we say when we part ways, loosely similar to “I’ll see you later” in English. But the structure of the word is what is important here. Properly translated, giga–waabamin means, “You are going to be seen later, by me.” The focus here is the other person, and the relationship between us.

It is in these structural nuances that I began to understand the ways in which my English-speaking brain has put the self—myself—at the center of my existence on this Earth. With this understanding came a deep sense of loss. I will never be a first-language speaker of Ojibwemowin, and all the ways in which I have oriented myself through my life are egocentric.

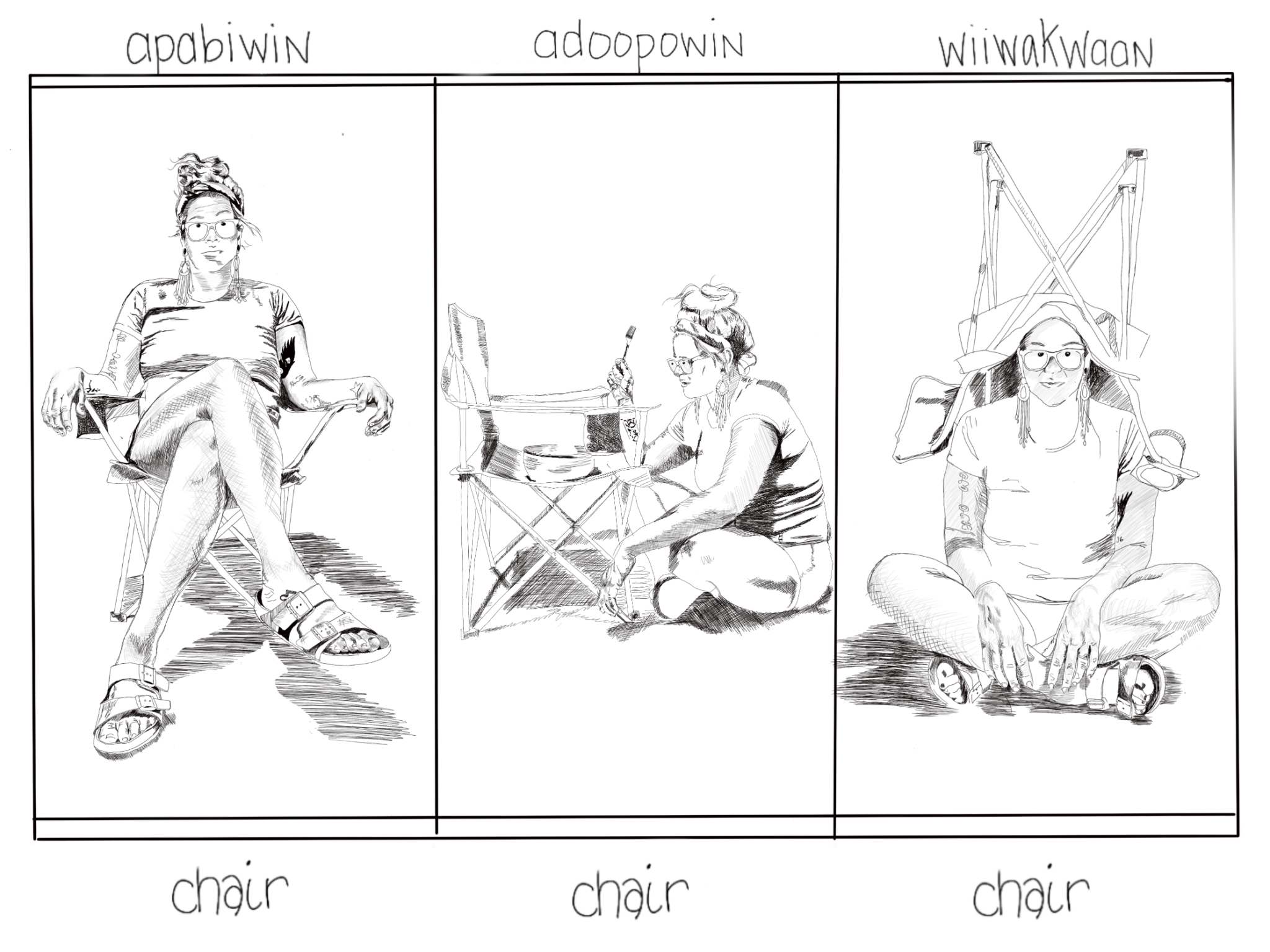

What if the word “chair” didn’t refer to an object for us to sit on, but a relationship between us and an object? In languages like Ojibwemowin, we aren’t the central reference point for all things; we are just one part of the world around us. “Bizaan-ayaa (She is Calm).” Artist: Alexandera Houchin

What if the word “chair” didn’t refer to an object for us to sit on, but a relationship between us and an object? In languages like Ojibwemowin, we aren’t the central reference point for all things; we are just one part of the world around us. “Bizaan-ayaa (She is Calm).” Artist: Alexandera Houchin

So, I tasked myself with unlearning these egocentricities. I started sticking Post-it notes with Ojibwe definitions on things around my home: the door, the oven, the faucet. But it was the Ojibwemowin word for chair—apabiwin—that really caught me up.

Ojibwe words are composed of several morphemes, so I broke down the word apabi and win: apabi, a verb meaning “she/he sits on something” and win, a suffix that turns the verb into a noun. I realised that if I sat on the table, that table could also be spoken of as apabiwin; or, if I ate food off my chair, it could be called adoopowin—which is also the Ojibwemowin word for “table.”

That’s because the way we relate to things is built into our language. What does it mean to me that a chair is a “chair” in English, if I’m not sitting on it?

The deeper I dove, the more confused I became. Why do we, as English speakers, use locatives like “in front of,” “behind,” “to the left of” and “to the right of,” phrases that are only useful from a single static perspective, rather than the cardinal directions (north, south, east, west) which can be used anywhere? A person from the Guugu Yimithirr tribe of Australia, for example, would tell you to “look west” or “head north,” rather than “look behind you” or “hang a right”—both of which are useless the moment you turn around.

This realisation made me angry, as if something had been stolen from me. Had I grown up learning to orient myself in relation to the world, maybe now I wouldn’t have to try so hard to be in relation to all things.

I will be seen later, by you. The author poses along the Akiing Anishinaabe trail. Duluth, Minnesota. Photo: Hansi Johnson

I will be seen later, by you. The author poses along the Akiing Anishinaabe trail. Duluth, Minnesota. Photo: Hansi Johnson

As I learned our language, I began to see the ways English fails to weave humility into how we communicate with each other. I found myself developing deeper relationships within my community in order to feel a deep connection to my own humanity and my own inadequacies. And I sought ways to bring these lessons into practice as a contemporary Indian using my passions outside of Indian Country.

I’d spent many years toiling with the idea that I either had to 1) choose to be an Indian and remain entirely in my tribal community or 2) pursue any other number of avenues and leave my Indigeneity back on my reservation. I’d felt so much pressure, imposed or not, to be great, to avenge the atrocities endured by my mother and aunt, my grandmother and those before them. They suffered so I could live this privileged life.

Little did I know that my affinity for cycling would provide that pathway. What started as bicycle commuting evolved into bicycle touring and eventually bicycle racing, until, in 2018, I won the women’s Tour Divide mountain bike race. I believe it was not because I was the fastest, but because it was the first time that I looked at a bike race through the lens of an Ojibwemowin language learner. The race and the racecourse weren’t so much about conquering and winning, as the English definitions would suggest; instead, I saw the course as a path toward ceremony and the people racing alongside me as my relatives sharing the same experience. As a 21st century Indian, I realised that this is how I hold space in a contemporary way.

Be it about a bike race or a children’s book, the language we speak reveals the way we relate to the world around us. As I continue to explore our ancestral language and teachings, I feel blessed to know that the secrets to leading mino-bimadiziwin, the Ojibwe concept of “the good life,” are woven into the way we live in relation to each other. It’s in that knowing and belief that I invite you to join me on this journey of decolonizing our worldviews.

Alexandera is a citizen of the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe and the current women’s single-speed mountain bike record holder for the Tour Divide mountain bike race, the Arizona Trail Race and the Colorado Trail Race.