Editor’s note: Prolific author and National Geographic magazine writer Doug Chadwick takes a fresh look at humans’ place in the natural world in his book, Four Fifths a Grizzly. In his accessible and engaging style, Chadwick approaches the subject from a scientific angle, with the underlying message that humans are not all that different from any other creature. He begins by showing the surprisingly close relationship between humans and grizzly bears, with whom we share 80 percent of our DNA. We are 60 percent similar to a salmon and 40 percent the same as many insects; 24 percent of our genes match those of a wine grape. At the same time, our bodies are teeming with organisms, separate from ourselves but upon which we are dependent for survival. Chadwick challenges anyone to consider whether they are separate from or part of nature. The answer is obvious: We are indivisible from all elements of a system that is greater than ourselves, and which should never be neglected, taken advantage of or exploited.

The following is an excerpt from Four Fifths a Grizzly, published by Patagonia in 2021.

There is so much nature in human nature that I can’t see where any more could fit in. To begin with, the number of distinctly human cells in each human being, variously estimated at 20 to 40 trillion, is equaled or exceeded by the number of microbe cells.

Close to a thousand different species inhabit your mouth. Several thousand species dwell within your digestive tract. Hundreds of species or more reside almost everywhere else. They coat your skin, line your pores, cling to your hairs, and especially abound in all the damp spots. Relax, I’m not judging; the same conditions apply to all of us, recently bathed or not.

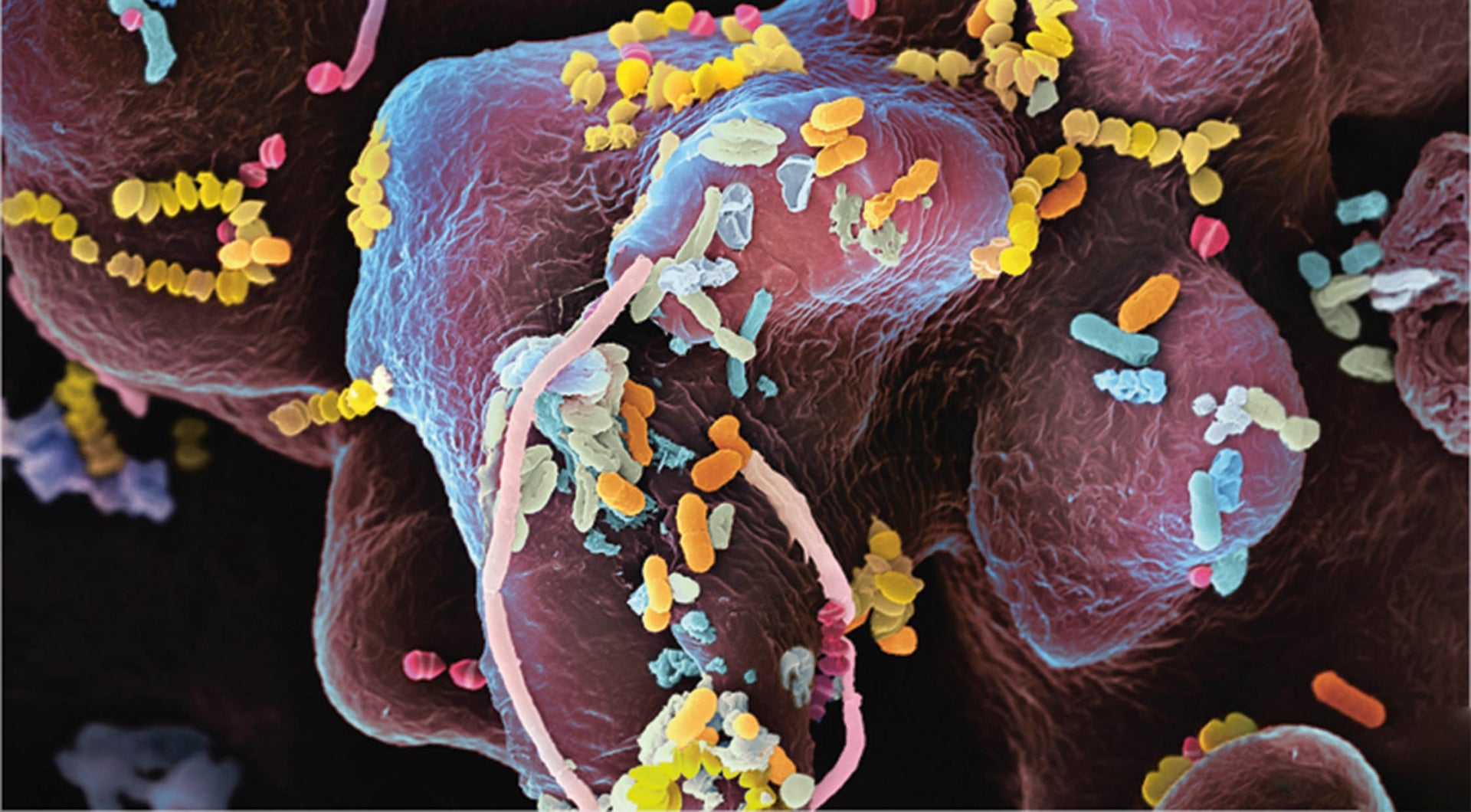

The oral mucosa is the mucous membrane epithelium of the mouth. It is populated with microbes, including many species of bacteria. Some taking up residence on the mouth lining (red) within days after birth. Harmful species form biofilms, like the plaque that encourages tooth decay, or colonize the crevices between teeth and gums, causing periodontal disease. Oral probiotics designed to boost the population of species that outcompete pathogenic ones could help prevent or reverse dental disease. Photo: © M. Oeggerli, supported by Pathology, University Hospital Basel and School of Life Sciences, FHNW.

The oral mucosa is the mucous membrane epithelium of the mouth. It is populated with microbes, including many species of bacteria. Some taking up residence on the mouth lining (red) within days after birth. Harmful species form biofilms, like the plaque that encourages tooth decay, or colonize the crevices between teeth and gums, causing periodontal disease. Oral probiotics designed to boost the population of species that outcompete pathogenic ones could help prevent or reverse dental disease. Photo: © M. Oeggerli, supported by Pathology, University Hospital Basel and School of Life Sciences, FHNW.

Granted, a great many of the microscopic life-forms we pack around are merely opportunists taking advantage of the nutrients to be found in and on a body as immense and relative to their size as the planet is to a person. Although some of our occupants are the kind that can make us sick under certain conditions, most are either harmless, assist us with bodily functions, or actively protect us against disease-causing germs and toxins. Many help us resist other types of afflictions as well. To choose a recently discovered example, the common and harmless skin bacterium Staphylococcus epidermidis produces a molecule that may arrest the growth of cancer cells triggered by overexposure to the sun’s ultraviolet rays.

A prime share of our gut microbes breaks down organic materials that we either can’t digest or don’t digest very efficiently. Some manufacture vitamins and other nutrients that we are either poor at making or unable to make and rarely get enough of from the foods we eat. As much as 80 percent of our immune system is situated in our gut, and its effectiveness appears linked to the balance of species in the microbiome there. And several kinds of common gut bacteria have been found to manufacture hormones and neurotransmitters identical to those produced by human cells and capable of influencing our moods and activities. More researchers are beginning to view our gut microbiome as something like a big, complicated, and still mostly mysterious gland.

A flurry of research now underway is aimed at discovering how the microbes we host may be influencing not only our general health but also our momentary cravings, moods, and—ultimately—our thoughts. The implications are obviously enormous. Who’s in charge of you? New findings may revolutionize medical treatments and personal wellness regimes, but the investigations are still in the preliminary stages. Meanwhile, think about adding more fiber from fruits and vegetables to your diet; it increases the variety of microbial allies in your gut and encourages their growth and metabolic activity.

Every person has about 22,000 (some put the estimate closer to 25,000) genes, the inherited set of chemically coded instructions that build and maintain a Homo sapiens. The spectrum of microbial beings we host possess at least 8 million genes among them, and I’ve seen estimates as high as 45 million. From this perspective, the full genome each of us carries around is a mosaic of human and microbe DNA, with the human part making up a very minor portion of the whole.

Two microorganisms, or microbes, viewed with a scanning electron microscope and artificially coloured for clarity. They are a human egg and sperm, and their meeting is the prelude to fertilisation. Credit: eye of science/ science source

Two microorganisms, or microbes, viewed with a scanning electron microscope and artificially coloured for clarity. They are a human egg and sperm, and their meeting is the prelude to fertilisation. Credit: eye of science/ science source

Bill Bryson calculates in his book The Body: A Guide for Occupants that if you were to uncoil all the DNA packed into your trillions of human cells and lay it end to end to form a single strand, it would extend for 10 billion miles from wherever you are to a point past Pluto. Though the DNA in each cell is the same, this is a stunning way to envision the total amount that a fully grown human being contains. And in reality, your greater self operates with even more. So, try mentally adding to that strand all the DNA from the microbes you host and picture a filament reaching still farther beyond this solar system toward the distant stars.

In addition to the number of life-forms that make their homes alongside the cells of our bodies, don’t forget the microbes dwelling within those cells as part of their makeup. Our cells can’t function normally without the organelles, or internal pieces, labeled mitochondria, for they carry out the energy-generating chemical reactions that are the basis of our metabolism. Just a few decades ago, scientists finally figured out that these organelles are actually modified ancient bacteria. As such, they add tens of trillions more microorganisms to the “you” that your mind conceives of as a singular being. Taken together, the invisible multitudes on and in us redefine every person as a kind of compound creature, an organism that is in reality a combination of organisms interwoven in more ways than we have yet found words to acknowledge.

“Where textiles are used to conceal, I use them to reveal,” says artist Rebecca D. Harris, who embroidered French knots to represent the microbes that coat human skin (but not that of the fetus protected in a womb). Photo: Rebecca D. Harris

“Where textiles are used to conceal, I use them to reveal,” says artist Rebecca D. Harris, who embroidered French knots to represent the microbes that coat human skin (but not that of the fetus protected in a womb). Photo: Rebecca D. Harris

This is not to say each person isn’t an individual with a unique physical appearance, temperament, set of experiences, and so on. Combined with the intense level of self-awareness humans possess, this distinctive identity is very real to us and lays a preeminent role in both our relationships with other people and our position in society. Yet, the importance we place upon our individuality becomes something of an obstacle to recognizing everything else that defines us. The microbes we are endowed with and the genes we have in common with other life-forms are key dimensions of the human being.

From a comfortable rain forest perch in a remote part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a young male chimpanzee strips bark for a meal. Photo: Ian Nichols

From a comfortable rain forest perch in a remote part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a young male chimpanzee strips bark for a meal. Photo: Ian Nichols

Humankind’s defining characteristics embody nature in other ways as well. Our nervous system, reflexes, senses, physical abilities, emotions, aspects of our social behavior and cultures, and even our thought patterns and decision-making abilities—many of the qualities we sum up as human nature—developed under the influences of predators, competitors, and the species we relied upon for food. Through the ages, whole communities of wild creatures large and small played parts in shaping who we are and what we do. They live on in modern people, just as part of what makes us human exists in the creatures around us today—in the genes, tissues, metabolic pathways, and behaviors we have in common. This is what makes us more than just human. This is what I mean when I refer to our greater selves.

Banner Image: Sometimes described as algae that live in glass houses, diatoms are photosynthetic protists that construct shells of pure silica. This marine species grows in clusters on seaweeds. Photo: Wim Van Egmond

____________________________________________________________________

Author Profile