Our best ideas come from being in the field. But sometimes simple problems inspire complex solutions.

At Patagonia, that’s been the case with the development of insulation. Down gets wet and loses its heat-trapping loft, and synthetics never quite achieve the same warmth, lightness or compressibility as down plumes. We’ve tried everything from treated down to synthetic fills that relied on various quilting constructions to prevent clumping. Yet none of these methods ever quite captured the best qualities of both, while successfully solving for the shortcomings of each.

PlumaFill’s spiral blasted filaments. Photo: Kyle Sparks.

PlumaFill’s spiral blasted filaments. Photo: Kyle Sparks.

Then, in 2007, our materials research and development manager discovered an interesting synthetic insulation made of microfilaments spiraling a central fiber that looked, felt and behaved like down, and tested out with better warmth for its weight than anything we’d previously worked with. Through extensive lab trials over a seven-year period, we found that this insulation, which we later named PlumaFill, proved to be highly compressible as well as 40 percent warmer for its weight than other leading synthetic insulations. Our Killer Wash testing standards demonstrated that after a simulated lifetime of use, PlumaFill suffered almost no loss in loft. This was impressive. Most synthetics we’ve tested or observed in the past either deteriorated or clumped into balls after washing, which causes cold spots, but this new fiber held up to every abuse we put it through. “Three years ago, I did a study of the synthetic insulations on the market that were supposed to mimic down,” says material developer Kristin Umscheid. “I found PlumaFill to be the only insulation that passed our durability standards and, in fact, surpassed other synthetic insulations.”

Senior product designer Christian Regester developing an early prototype. Photo: Kyle Sparks.

Still, our designers were stymied by how to use it. Various shell fabrics prevented the insulation from lofting to its full capacity, and, when paired with a shell, different patterning constructions caused the strands to wrap around each other or lose loft. It took another year of work for our senior product designer Christian Regester to develop a structure that locked each strand of insulation into place to maintain the maximum warmth-to-weight combination possible while using the least amount of insulation. The perpendicular, discontinuous stitching pattern prevents shifting and reduces both weight and the potential for cold spots.

“What exists now is a jacket that speaks to our ethos of design. We set out to solve a problem, and after 10 years of dedicated tinkering and serious refinement, we succeeded.”

The team then developed a pattern to make fewer but larger pattern pieces, which allows heat to move more freely inside the jacket. “The quilting pattern was developed through a process of testing the weight, loft and durability at varying intervals,” says Regester. “After determining the best quilt dimension, we worked to construct it in a way that maintained airflow within the garment and used only the minimum amount of thread needed.” We paired this construction method with the lightest woven shell fabric we’ve ever used, and when we tested it again, the numbers were astonishing. “It was the lightest fabric we found that passed our testing standards and that we could execute in production,” says Umscheid. The Micro Puff Jacket was lighter and warmer for its weight than any of our down products, and the compressibility propelled it into a category of its own. The pattern also incorporates learnings from our styles with the highest-efficiency fabric yields, allowing us to create less scrap and keep fabric out of the landfill.

A prototype being tested in the lab for warmth. Photo: Kyle Sparks.

A prototype being tested in the lab for warmth. Photo: Kyle Sparks.

Alongside this in-house refinement, we tested it in the field, mocking up prototypes to refine the design and asking our athletes to climb, run, ski, plan multiday expeditions and generally beat the heck out of the early models. Many testers thought the jacket actually was down and were surprised to learn it wasn’t. “We got a good idea through our lab testing that we had something special, but then we needed to build prototypes and test them in the field,” says Regester. “Everyone that got their hands on one didn’t want to give it back.” Consistent feedback also spoke to the weight for warmth. “I realised pretty quickly we were onto something,” says Kelly Cordes, climbing ambassador. Three years on, it’s still at the top of the rotation for many of our testers.

Reports from the field

“What’s not to love about this? Lighter, softer and seems warmer. Goes straight to the top of the rotation.” — Steve House.

“Feels like down. In testing, I remember it being as warm as a Nano, but it’s about 20 percent lighter, so much greater warmth-to-weight ratio.” — Kelly Cordes.

Colin Haley testing the Micro Puff’s warmth in the field. Alaska Range. Photo: Mikey Schaefer.

Colin Haley testing the Micro Puff’s warmth in the field. Alaska Range. Photo: Mikey Schaefer.

What exists now is a jacket that speaks to our ethos of design. We set out to solve a problem, and after 10 years of dedicated tinkering and serious refinement, we succeeded – all the way down to the number of quilt points. “Building a durable product that’s also as light and warm as possible while maintaining loft when wet has been the goal of mountaineers since climbing mountains began,” says Regester. “Sometimes the best ideas take time.”

This story first appeared in the January 2018 Patagonia Catalog. Visit patagonia.com.au to see the full line.

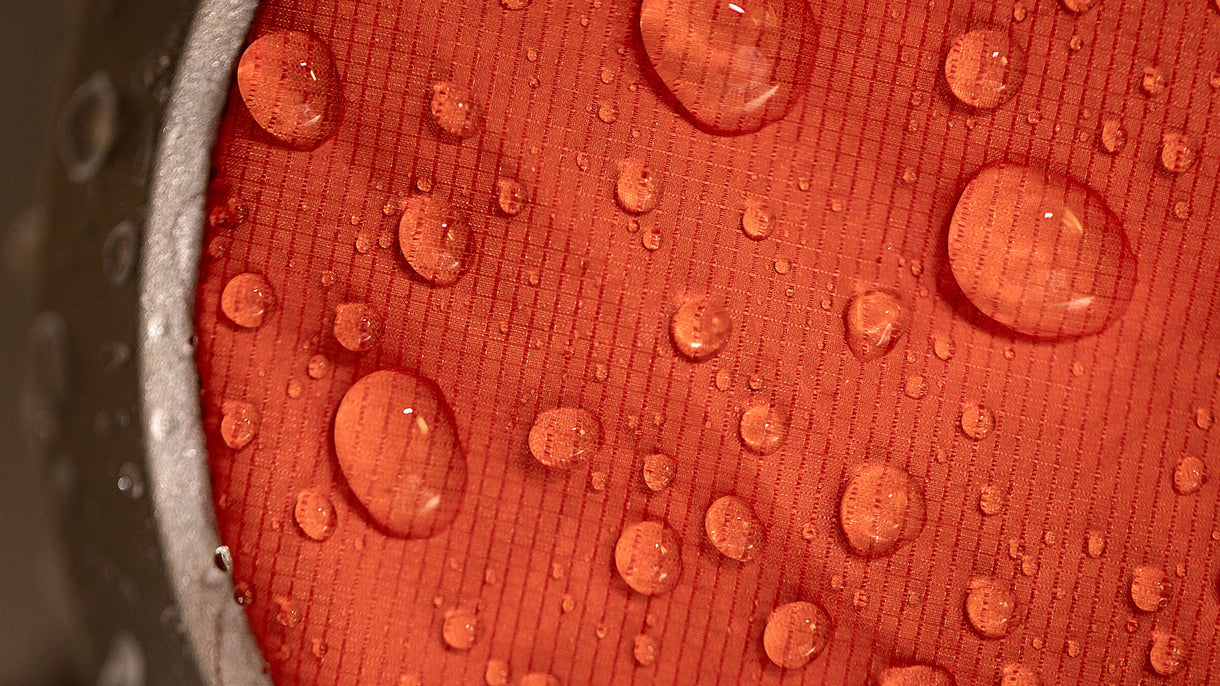

Banner image – Patagonia material developer Kristin Umscheid studies PlumaFill’s potential at the Patagonia headquarters in Ventura, California. Photo: Kyle Sparks.