History often repeats itself. It certainly seems that way in Warburton on Melbourne’s forested, northern fringe. Here, rugged, bearded men in flannelette shirts walk the streets like lumberjacks from another age. Old style shop fronts sell wooden antiques and children run freely through stands of Mountain Ash (Eucalyptus regnans), the tallest flowering plant in the world. Friends sit down and share lunch made up locally sourced produce – cheeses, wine, and sourdough bread.

All in all, it is a scene from a different era, a portrait of the quintessential timber towns of Victoria’s Central Highlands. But this is 2022 and those towns – Healesville, Warburton, Powelltown among them – are a long way from the era when native timber harvest was the key employer in the region.

Instead, the towns have transitioned and are now filled on any given weekend with trail walkers and mountain bikers keen to leave behind Melbourne’s immense urban sprawl and immerse themselves, as so many have over the years, amongst the man fern and sassafras that abound here.

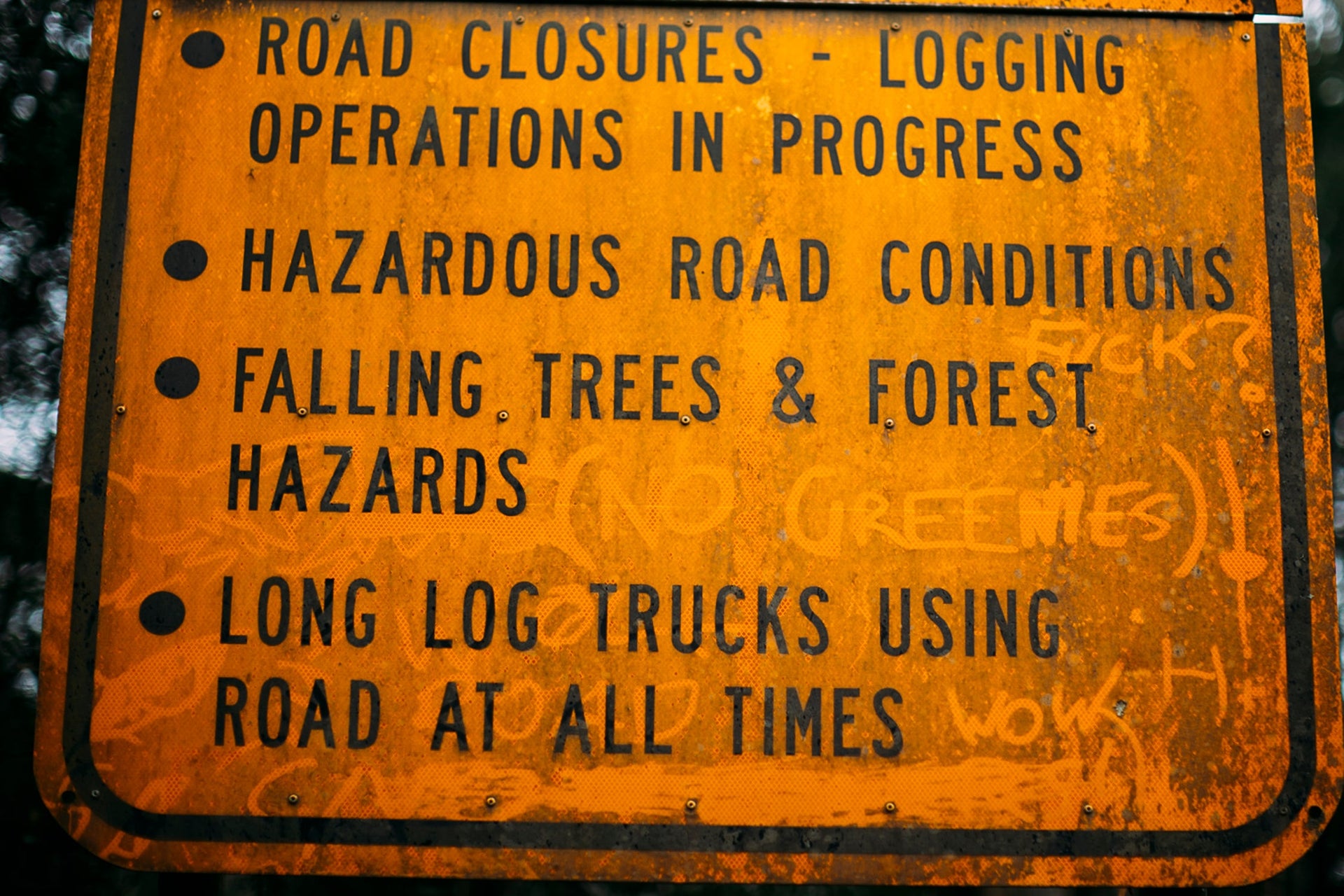

But history often repeats itself in unusual ways. While the region’s economy is benefitting from people enjoying this natural landscape, just over the hill, industrial scale logging is continuing to knock it down. The irony is, compared to the halcyon years when the timber industry was providing the backbone of the state economy, native forestry is not even remotely profitable today.

Last financial year, VicForests – the agency which is responsible for managing the harvest sale, and regrowing of timber from state forests on behalf of the Victorian state government – registered a $5 million loss. The year before, it lost $7.5 million. This didn’t stop the state government providing $18 million to VicForests’ operations last year and $21 million the year before. While this is described by VicForests in a recent annual report as “other income from Victorian Government entities”, these funds are, in essence, subsidies that are allowing a loss-making enterprise to continue.

Through this, there remains a lot of confusion in the public mind about what actually happens to the trees harvested from native forests. Many assume that the timber makes its way to the local building industry to meet its voracious demand for house frames and floorboards. With housing crises across the country, demand for resources is only expected to rise.

However, demand for building timber is almost completely met by plantation stocks. And those thinking native trees feed solely the fine wood trade – turned into bespoke cabinets, tables and wardrobes – are also mistaken. The majority of native trees felled in Victoria are woodchipped or pulped and shipped offshore.

From a commercial viewpoint, logging of native timber is on its knees. Native forestry has become less and less profitable since mid-last century when thousands of workers were employed to supply timber to the sawmills of Victoria. Fast forward to 2017, and there were just 506 direct jobs associated with VicForests across the entire state.

VicForests conceded – almost a decade ago – that even in the East Gippsland Forest Management Area, Victorian forestry’s heartland, native timber harvesting operations “have not been profitable… for many years.” Such shortcomings in the current business model have helped to advance the environmental and economic cases for ending native logging in Victoria, culminating in the Victorian Labor Government announcing in 2019 that logging will be phased out over the next decade.

But for logging to limp towards this eventual finish in 2030, it has been estimated that it is going to cost Victorians $192 million in subsidies. Twenty-thirty is a significant year for environmental commitments. This ending of native forest logging sits alongside the Victorian government’s pledge to reduce carbon emissions by a full 50 percent by that year.